12 January 2026

The circle is a core part of teaching students geometry, as understanding its many properties is essential for many real-life applications, including design and engineering.

A circle is a closed two-dimensional (2D) shape where each point of its boundary has the same fixed distance from the centre. The word comes from the Latin term “circulus”, which translates to “small ring”. The shape of a circle is created from a connected series of points set at a fixed distance from a fixed central point.

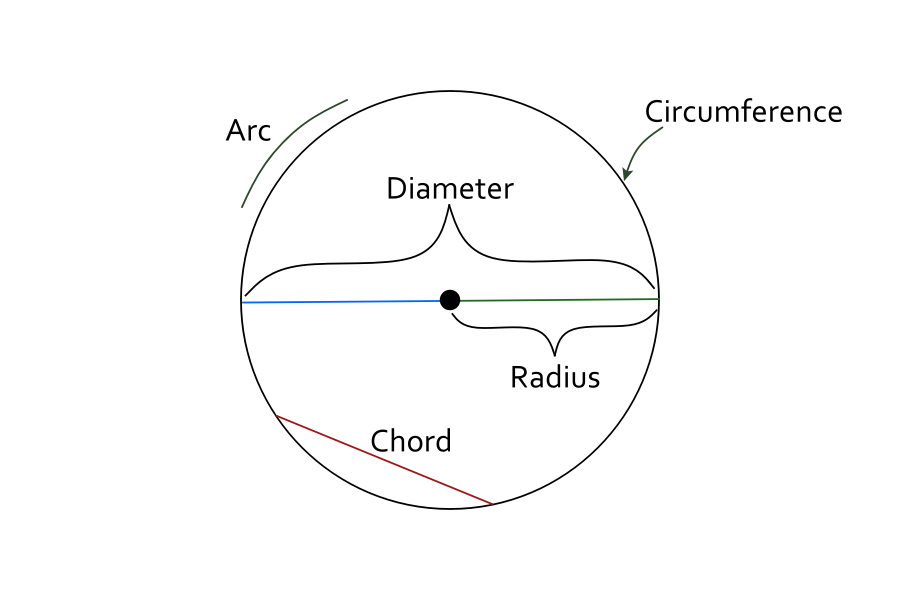

The graphic below helpfully illustrates a circle’s radius and diameter, as well as other core components that make up a circle.

The distance from the circle’s boundary to the centre is known as the radius (r). Meanwhile, the longest distance between any two points on the circle, passing through the centre, is known as the diameter (d). When two points in a circle are connected by a line, but do not cross the centre, it is known as a chord. Conversely, if two points along the circumference are connected, it is an arc.

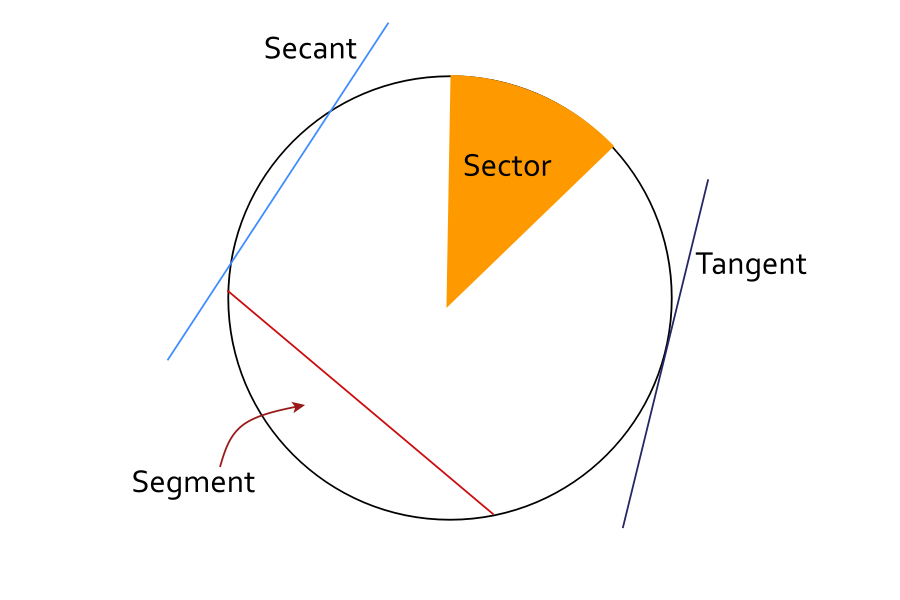

Combining these fundamental aspects allows us to identify other parts of a circle. For one, the area enclosed between two radii (the plural of radius) and an arc is known as a sector. Meanwhile, a segment is the area enclosed by a chord and an arc.

Lastly, tangents are lines that touch a single point of a circle’s circumference, while secants are lines that cut through the circle at two points.

Students will need to learn these formulae to calculate various aspects of a circle. Here is a guide to find the area of a circle and other related shapes.

Diameter = 2 × r

Circumference (Perimeter) = π × d

Alternatively:

Circumference (Perimeter) = 2 × π × r

Area = π × r2

Note that π (pi) equals 3.14, “r” is the circle’s radius, and “d” is the diameter.

Area = 1⁄2 × π × r2

Perimeter = 1⁄2 × π × d + d

Area = 1 ⁄4 × π × r2

Perimeter = 1 ⁄4 × π × d + r + r

To find the sector’s area:

A = θ ⁄ 360 × π × r 2

θ represents the angle of the arc, measured in radians.

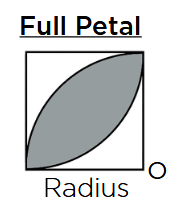

A boomerang is represented by the shaded part in the following graphic:

Area = Square – Quadrant = (r × r) – ( 1⁄4 × π × r2 )

Perimeter = 1⁄4 × π × d + r + r

For the arc length:

L = θ ⁄ 360 × 2 π r

Area = Quadrant – Triangle = ( 1⁄4 × π × r2 ) – ( 1⁄2 × r2 )

Perimeter = 1⁄4 × π × d + Side of square

Area = Half Petal × 2

Perimeter = 1⁄4 × π × d × 2

A circle is a closed shape with a single curved face. It does not “open up” or break at any point, and is a continuous line that curves into this circular shape. There are other theorems and properties that students should also note, as these can be useful in solving maths questions related to circles.

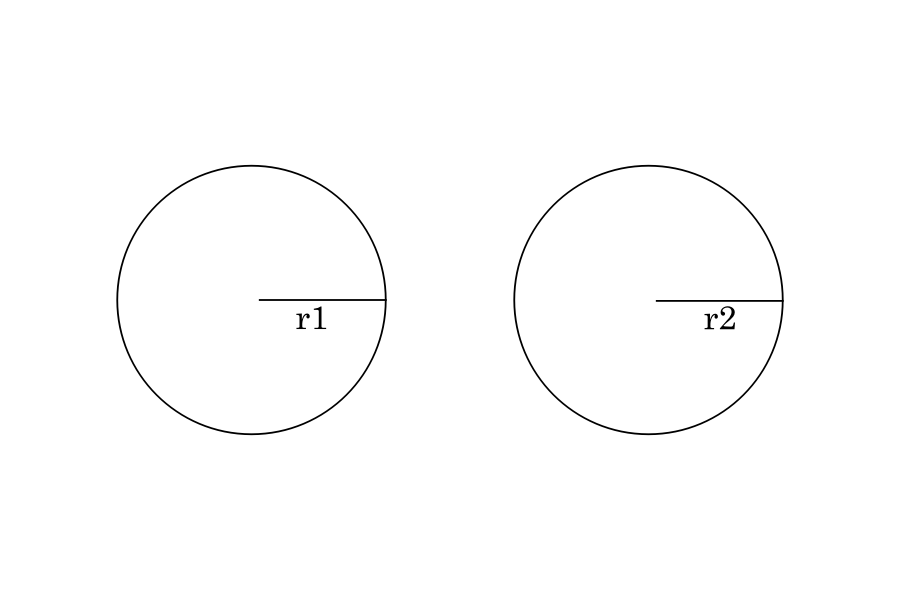

Two circles are only considered congruent (identical in shape and size) if they have the same radius. In the graphic below, if r1 = r2, then both circles are congruent.

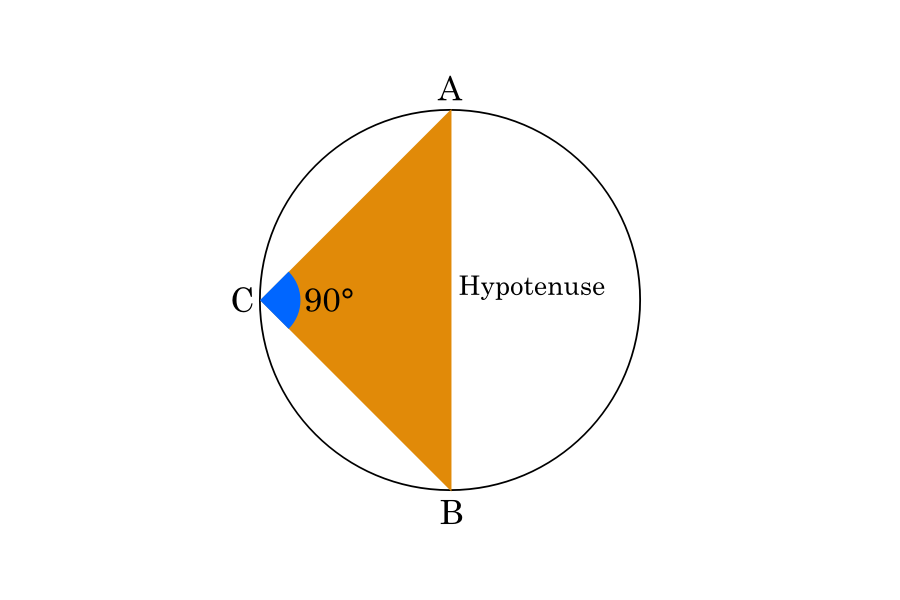

If a triangle’s hypotenuse is drawn as the diameter of a circle, then the angle opposite to the diameter is always 90°.

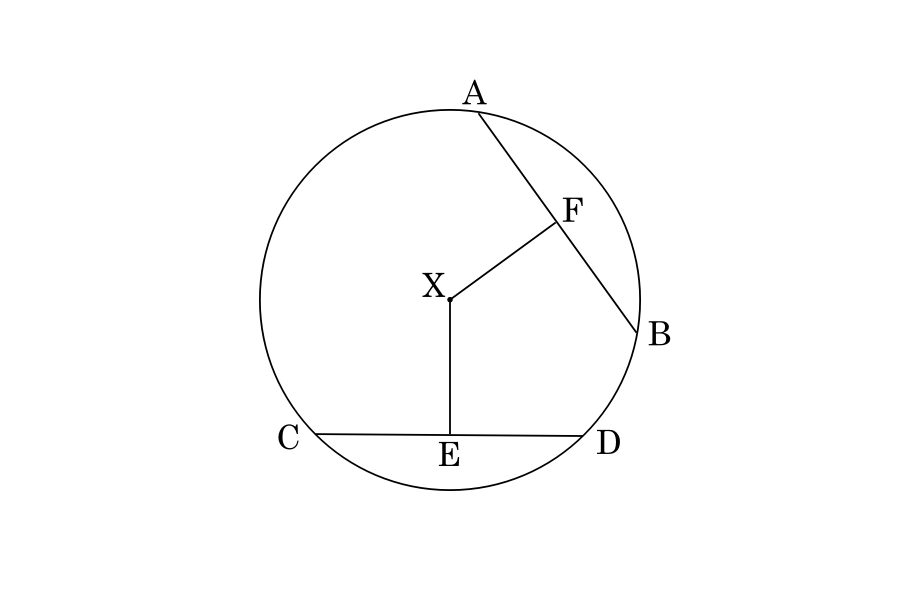

If two chords are of equal length, they will always be at the same distance (equidistant) from the circle’s centre.

Thus, if AB = CD, then EX = FX.

Additionally, using the figure above, if lines EX or FX are perpendicular (intersecting to form right angles) to AB or CD, respectively, then each line will bisect its respective chord into two equal parts.

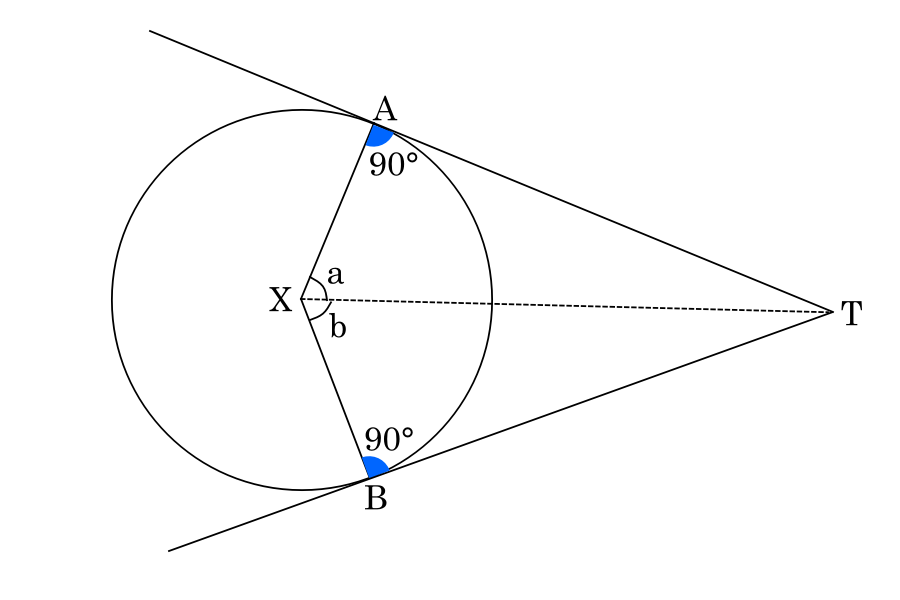

If two tangents start from the same external point and connect from T to the circle’s centre, X, then both tangents are of equal length. Moreover, the angle between a tangent and a circle’s radius is always a right angle.

Lastly, if a line joins an external point (T) from or to the circle’s centre (X), it bisects the angle between the tangents. Therefore, TX bisects ∠ATB and ∠a = ∠b.

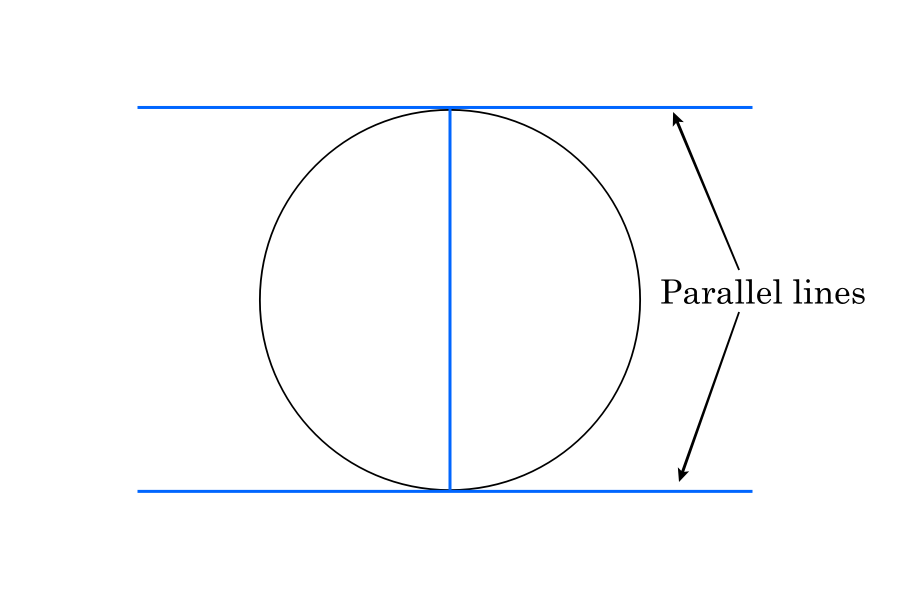

Speaking of tangents, if two tangents extend towards each end of the circle’s diameter, both tangents are parallel to one another.

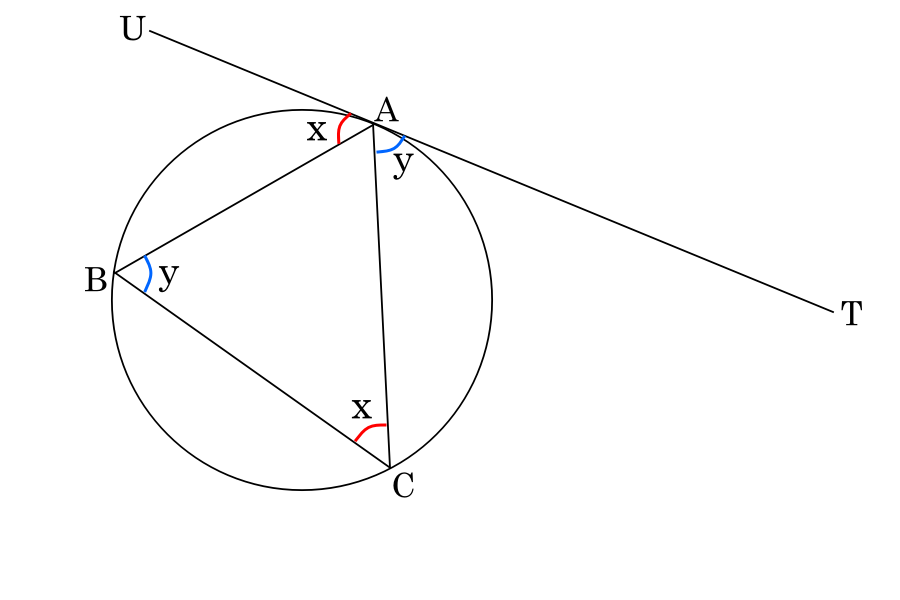

Note that, in the figure above, TU is a tangent, and AB is a chord. The angle formed between the tangent and the chord in one segment (for example, ∠TAC) is equal to the measure of the angle opposite in the alternate segment (in this case, ∠ABC).

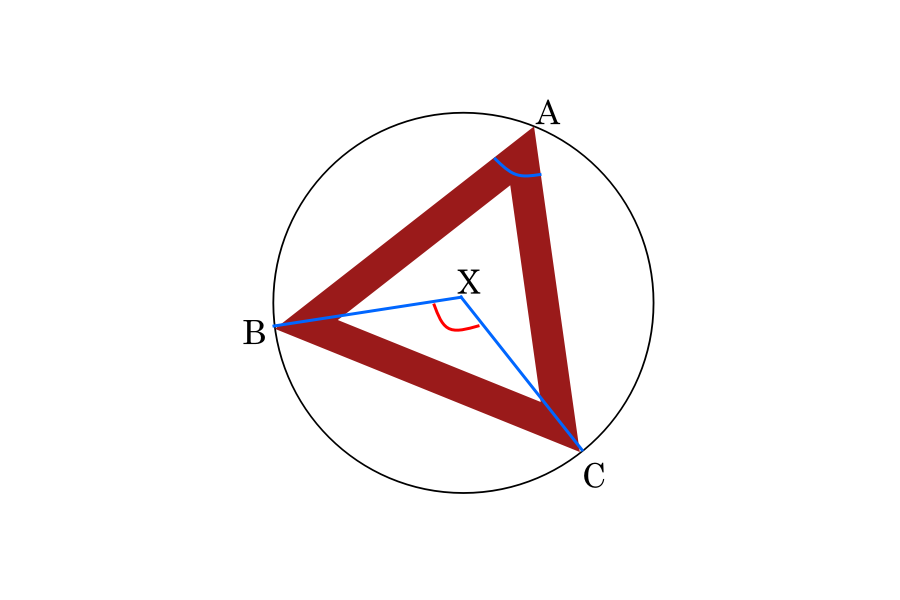

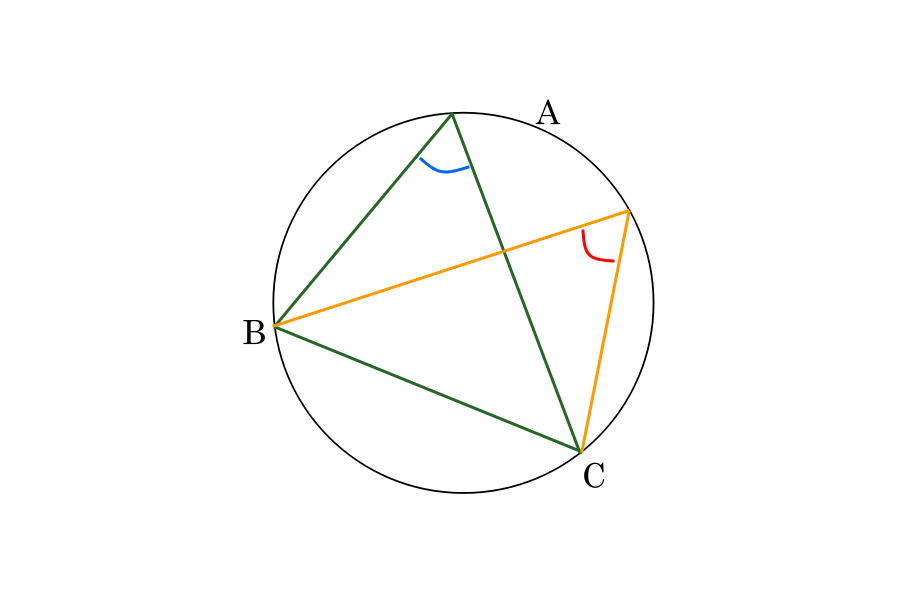

The angle at the centre is twice the angle at the circumference when subtended by the same arc.

In the above example, ∠BXC = ∠BAC x 2.

Angles of the same segment formed from one chord are equal.

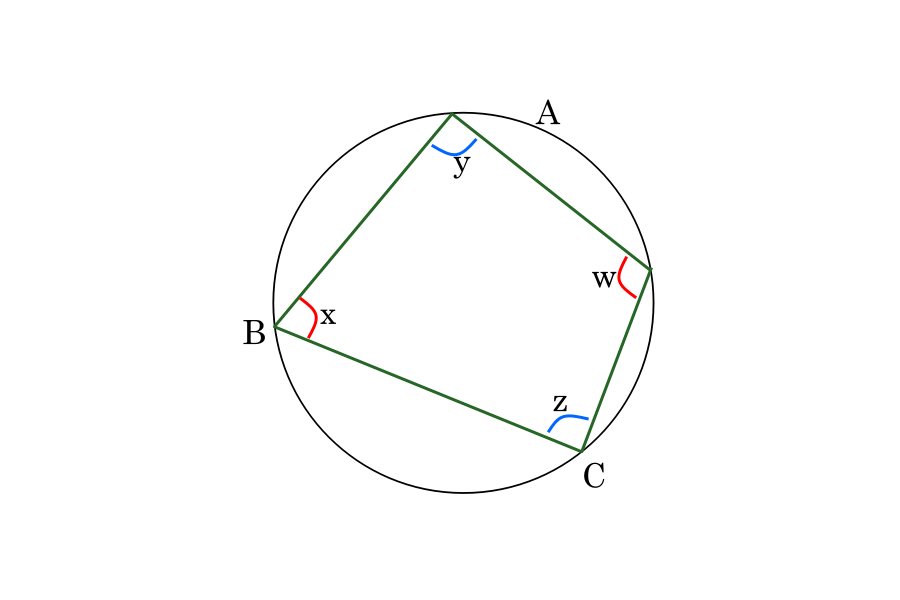

Meanwhile, angles in opposite segments add up to 180°. Using the example below:

∠w + ∠x = 180°

∠y + ∠z = 180°

This method is also known as the cyclic quadrilateral theorem.

Matrix Math provides personalised maths tuition to help secondary students strengthen their fundamentals across various topics, including circles and geometry. Contact us today to learn more about our teaching approach!